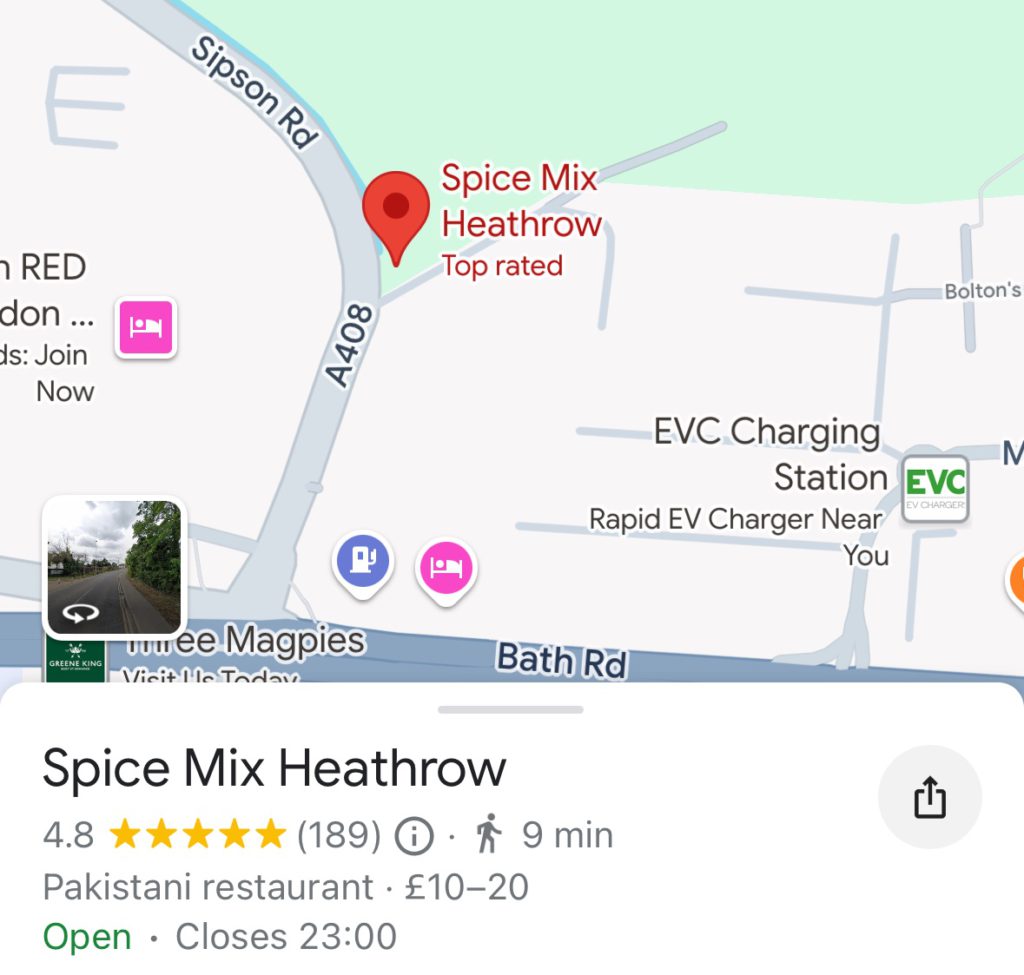

Spice Mix, 611 Sipson Road, West Drayton UB7 0JD

I find myself on a dull Tuesday evening in the London Borough of Hillingdon, an excellent staging post ahead of a visit to a certain nearby airport for sundry work purposes that are of little interest here. Previous research into lodgings along the Bath Road had alerted me to an interesting venue on the way to Sipson:

Could this be Pakistani curry within easy walking distance of the strip of airport hotels that line Heathrow’s northern flank? I knew I would have to investigate.

I drove up from the south coast under apocalyptic skies, accompanied throughout the journey by stop-start (but not much in the way of stop) torrential rain. Dashing from my parked car to the hotel entrance entailed getting thoroughly soaked. Although my goal was only ten minutes’ walk away I wondered if this was an option in these conditions.

After checking in I noticed something of a sucker’s gap on the weather radar. It was now or never. My confidence in making the journey without drowning received a further boost on the discovery of an ingenious machine in the lobby that would hire me an umbrella for the princely sum of two quid. Suddenly I was all set.

I made my way along Bath Road, constant and thunderous traffic keeping me company as I dodged the puddles and spray. As I made my way up Sipson Road my goal gradually revealed itself around the corner – here was Spice Mix, sharing its salubrious location with an airport parking firm and a hand car wash.

Presenting myself at the building shown on Google Maps, I noticed a sign directing me further into the car park. A portacabin beckoned from a corner. Strolling in, I found it empty. The actual kitchen was to be found in the next building, along with a member of staff in the midst of a phone call, who espied me as I wandered around. He bade me wait for him in the portacabin.

Phone call still underway, the man joined me in the portacabin to take my order. This was to be lamb karahi, plain rice and a butter naan. I had an important question – did the karahi contain the devil’s vegetable (capsicum)? It did not. But – and this was most important – how spicy did I want it? I offered “desi spicy?” – this was understood. “Medium?” he replied. “And a little bit more.” We had an understanding.

I took a seat and appraised my surroundings. This was no frills in the extreme, a curry caff in its purest sense. Others arrived, and similar negotiations were entered into.

After a decent interval my food appeared. This would be an extremely moist karahi, to the point of it having shorva as opposed to masala. It was bedecked with a garnish of julienned ginger, bullet chillies and a sprig of coriander. The bread was served quartered. The rice was in abundance, and would probably be too much for me. Dipping the bread into the shorva revealed spice but not much in the way of seasoning.

I should note at this point that I had recently recovered from a bout of the ‘vid during which my sense of smell went temporarily astray. While it has now returned there is still a possibility that the taste buds might not be completely back to full function although I think they are mostly working ok now.

Getting stuck in, I decided my method of attack would be to transport the rice from its bowl to sit atop the shorva. The lamb was tender, with one piece on the bone of the eight or nine present. I got the impression that it and the shorva had been introduced only recently. The spice built nicely, however the seasoning was still rather lacking. It was however a perfectly serviceable curry, and one I was enjoying eating.

The bread was an interesting proposition. While it certainly had butter on it and tasted buttery, it was a stodgy old thing and not quite what I had hoped it would be. I considered I would possibly have been better off forgoing the bread in favour of the rice, which was nicely infused with the aroma of cardamoms, one of which I narrowly avoided biting into – always the surprise nobody wants.

I managed all the meat and most of the shorva, but as I predicted an amount of the rice had to remain uneaten. This was perfectly good, honest food, which set me back £13.90. Not unreasonable by any means. The man I paid was a different fellow to the one who had taken my order and prepared the food. I found him as I left, in the same window through which he had originally espied me. “How was it?”, he asked. I told him I had asked for desi, and that was exactly what he had given me.